Findings

Open North’s second data governance workshop produced several important findings on key issues we have seen occur regularly across our network of local governments. In this research blog post, we will show that difficulties around building internal alignment, establishing effective leadership, and identifying effective and rightsized implementation strategies can be solved. Based on our workshop conversations and extensive experience working with local governments on data governance and digital strategy, we have identified three tactics that are at the heart of most successful organization-wide data governance projects:

- A strong foundational project that can serve as a focal point for working through organization-wide data governance issues. An open data program as in Cape Town or Montréal is the most commonly mentioned example, but data inventories and data quality also feature regularly. Such projects provide a concrete, practical opportunity to experience the value of data governance, build appropriate governance structures, and improve digital capacity and literacy through firsthand involvement.

- Internal stakeholder engagement that pairs a digital maturity and gap analysis assessment with an in-depth needs assessment from individuals and business units. As we saw with Montréal and Toronto, this is not simply a data gathering exercise, but far more an opportunity to involve and collaborate with stakeholders across the organization. Collaboration, as Edmonton advanced it, is crucial to the success of an organization-wide data governance implementation plan.

- A digital strategy that puts the synergistic combination of tactical components and guiding principles at its center. Cape Town, for example, connected its digital strategy around data as an asset for decision-making with a series of concrete projects throughout the pandemic. This built up the basis and buy-in for more organization-wide data governance development. Montréal and Toronto have a digital charter or frameworks that stemmed from successful tactical work, and now serve as aligning platforms for deeper work around master data, data architecture, data flows, and other advanced data management projects.

Data Governance for Local Government

On March 15, 2023, Open North’s Community Solutions Network hosted its first workshop on data governance for local municipalities. The goal was to conduct a wide-ranging discussion amongst our members and identify how they were approaching the topic of data governance, what their goals and needs and barriers were, and with that launch a series of workshops that would support their projects.

The workshop was headlined by two of Open North’s data governance partners, Cities Coalition for Digital Rights and Open and Agile Smart Cities. These partners underscored the importance of a rights-based approach to governance and of digital standards, respectively, before the workshop transitioned to a conversation amongst participants about their data governance work. The presentations in combination with the subsequent in-depth community of practice conversations led to a series of critical insights. These can be found in detail in the blog post that followed. These insights also caused several of the participants to reach out to us and ask about best practices for developing organization-wide data governance in local government.

As a result, we decided to bring our expertise in working on data governance across the country together with leading local governments for a second data governance workshop. We invited several partner cities who have had success in doing just that to speak about their experience and be part of another discussion with our community of practice members.

On August 3rd, 2023, we held the second workshop with a panel of speakers from Cape Town, Montréal, Toronto, and Edmonton. Each speaker provided a detailed look at how their organizations had undertaken comprehensive data governance reforms before complementing the panel with an hour-long Q&A session. The whole workshop was astoundingly rich in lessons learned, best practices, and strong potential approaches to such an undertaking. The recording and transcript are available online, but in this blog we’d like to show the several important solutions this workshop provided to the issues identified in the first workshop.

Issues and Solutions

The first workshop identified three key issues local municipalities are grappling with, which include:

- how best to build leadership for a project,

- how to create alignment amongst the stakeholders, and

- how to develop an implementation strategy that embeds current best practices and future-ready maturity from the ground up.

Many of the solutions the organizations developed acted on two or three of these issues simultaneously. To best underscore this kind of synergy we will present their approaches ordered by organization, rather than by issue as we have above.

Cape Town, South Africa

Cape Town began its digital transformation journey in 2002 with a concerted move towards a centralized SAP-based ERP system. This development provided the foundation for many key subsequent projects; however, according to Hugh Cole, a key development was the implementation of an open data program. This strategy of centralizing systems and then establishing data at their centre laid the tangible groundwork for a digital strategy that could align stakeholders around the value of data as a municipal asset.

The first internal iteration of this strategy was in place a year before the COVID-19 pandemic began, and the city chose to demonstrate the approach’s validity – and so build further alignment – by working on clear use cases that leveraged data to provide valuable support to city operations during the pandemic. By weaving together strategy and practicalities, they were able to create alignment around their strategy.

At the same time, the city is looking to institutionalize a more dedicated data governance committee. While they have been lucky in the past to enjoy the support of chief executives for their digital transformation projects, much of the work has been done “off the side of their desks” and they are reaching a point at which having a purpose-driven data governance committee that includes chief executives for direction, implementation, and dispute resolution is necessary.

Edmonton, Alberta

Wojciech Kujawa outlined how his team at the city of Edmonton undertook a clear implementation strategy for organization-wide data governance, one based on always identifying the value add of data governance, and consistently seeking collaboration with business units as the foundation for more expansive development.

To this end, Kujawa and his team began with a data governance maturity assessment of the city and used the results to identify points of greatest benefit for data governance work. His approach was that people are busy, and data governance is not a priority for them; it is important to show the value add, to bring that improvement directly to them.

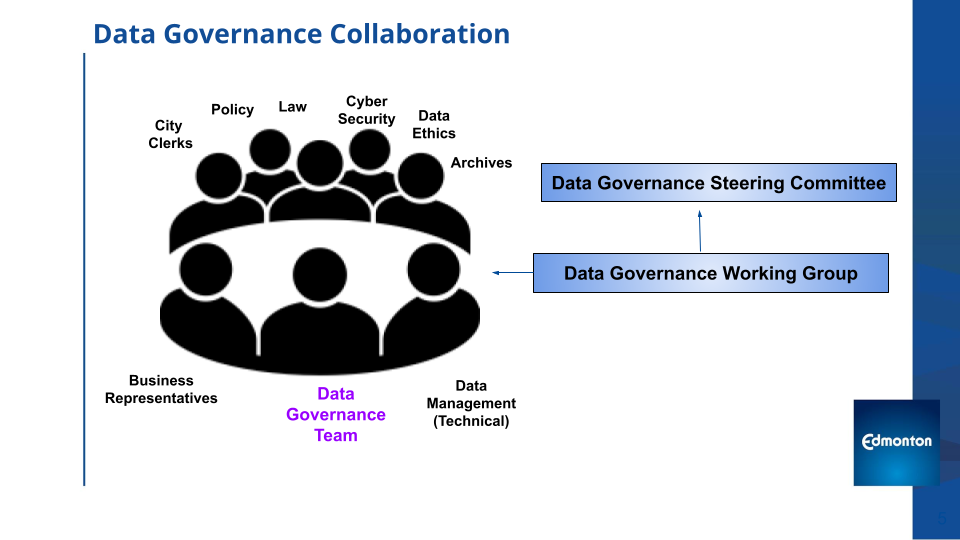

In a strong complementary strategy, the maturity assessment also showed that many roles in the organization already involved data governance; they just weren’t being understood as such. So, in addition to making the value add clear, his team also embarked on a deeply collaborative data governance implementation strategy that sought to achieve the following:

- involve these individuals directly the data governance development through a data governance working group and a superordinate data governance steering committee (see image 1), and

- also re-articulate roles to be more clearly conceptualized as undertaking data governance. This dual-stroke strategy created strong alignment in the organization, and recently resulted in the finalization of the data governance framework in which this organization structure is now officially articulated.

While this approach was primarily about strategy and alignment, their emphasis on collaboration and value also has interesting lessons for leadership. Kujawa said that for them, keeping leadership in the working groups and the committee emphasizes collaboration and helps maintain alignment; introducing an executive-level position like a chief data officer would actually undermine this cohesion and be detrimental to the process, particularly for a city on the medium to smaller size.

Toronto, Ontario

The case of the City of Toronto is a very instructive one for several reasons. As Nabeel Ahmed outlined, Toronto is an undeniably big city with many business units, each with a large staff and very deeply established infrastructure, practices, and cultures across large portfolios. In addition, Toronto has also had a highly revealing involvement with Google’s subsidiary organization, Sidewalk Labs, resulting in a several-year-long, highly contentious bid to redevelop a section of the city “from the internet up,” as Sidewalk Labs put it. This saga has been documented in great detail and has had numerous implications; for data governance, it resulted in the development of the Digital Infrastructure Strategic Framework that places data governance at the core of the city’s digital transformation.

For the purposes of this data governance workshop and research blog series, what’s instructive about this is not just the crisis leading to leadership’s investment in a serious data governance framework, but also how the new framework’s developmental approach differed from the old. According to Nabeel, attempts to develop such a framework had been made in the past, but had stalled due to lack of alignment. In this successful iteration, they didn’t just rely on a renewed push from above, but also conducted extensive internal maturity assessments, gap analysis, internal engagements through questionnaires, staff needs assessments, and jurisdictional scans. This created substantial internal alignment, particularly around the issue of data quality, that in combination with leadership support led to the successful development of the framework.

The team is now building upon this strategy and is charting a strategy that involves working through data management technical but critical issues like master data, data quality, metadata, and data standards and placing them in a 3-5 year plan while also supporting business units and their immediate needs.

Montréal, Québec

Montréal’s approach to developing organization-wide data governance shares a number of similarities with the other three cities but – as the others do too – it also differs in a few key ways. In 2020, Montréal launched its 10 year strategic plan, in which the central role of data and digital technologies is clearly positioned. However, as Miranda Sculthorp explained, the insight to do that rests upon years of experience developing the city’s open data program. Establishing a data inventory, cataloging data, working through data quality issues, and all the other essential data management aspects necessary for a functional open data program created a strong understanding in the city of the importance of data – and the realization that governance needed to be extended from the end of the data cycle, with which open data programs concern themselves, to the entire lifecycle became the foundation upon which a more broadly scoped data strategy could be envisioned.

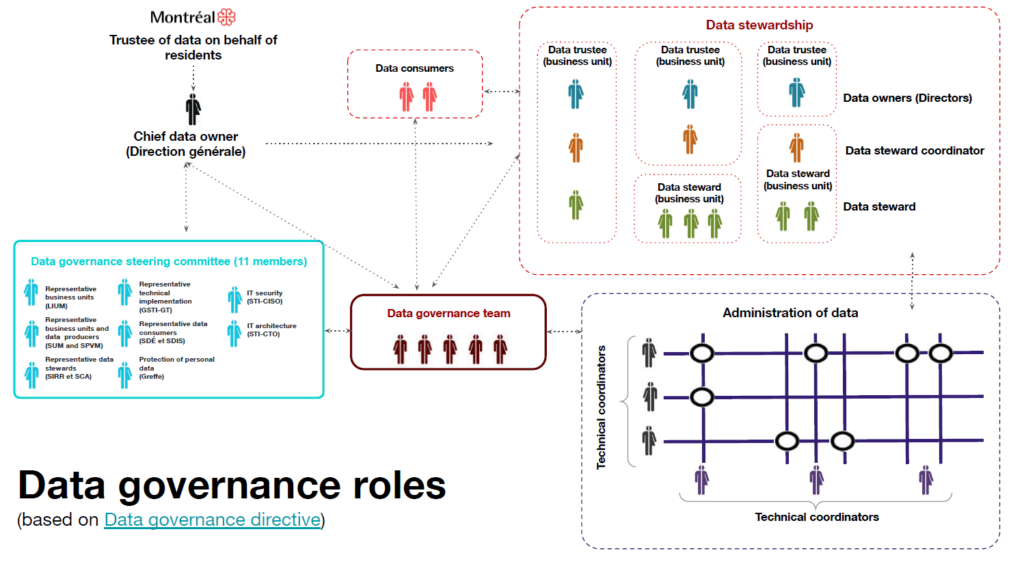

This strategy led them directly to considering the centrality of a well articulated data governance framework. They developed their “data governance directive” around the three core functions of data ownership, guiding principles, and roles and responsibilities. Establishing functional roles and responsibilities is fundamental to Montréal’s data governance approach, and their organization structure is outlined in the image below:

As the diagram shows, Montréal’s approach includes a detailed distribution of roles and responsibilities that functions to involve business units and individuals from across the city in data governance efforts. However, as Miranda explained, their approach wasn’t a simple top-down leadership strategy for alignment, but actually involved extensive internal stakeholder engagement and change management. In developing the directive and its implementation, they worked closely with the business units to not only understand their needs, but also – with the help of a change management expert and a human-centric design expert – ensure that policies, procedures, and resources were accessible, understandable, and tailored to the units’ needs.

Analysis

In each of these four cases, the cities took a different combination of approaches around alignment, leadership, and digital strategy. However, what they all show is that each of these elements is essential, and that they can – and should – be activated around clear, tangible, obviously valuable data governance projects, and then scaled from there. The “start small and scale” maxim is by now well-established wisdom in governmental digital transformation, but being able to identify where to start to succeed effectively and scale sustainably is key. These four cases, and our extensive work with communities and local governments across Canada, show that while there is no one silver bullet formula, there are several factors that consistently recur:

- A strong foundational project that can serve as a focal point for working through organization-wide data governance issues. An open data program as in Cape Town or Montréal is the most commonly mentioned example, but data inventories and data quality also feature regularly. Such projects provide a concrete, practical opportunity to experience the value of data governance, build appropriate governance structures, and improve digital capacity and literacy through firsthand involvement.

- Internal stakeholder engagement that pairs a digital maturity and gap analysis assessment with an in-depth needs assessment from individuals and business units. As we saw with Montréal and Toronto, this is not simply a data gathering exercise, but far more an opportunity to involve and collaborate with stakeholders across the organization. Collaboration, as Edmonton advanced it, is crucial to the success of an organization-wide data governance implementation plan.

- A digital strategy that puts the synergistic combination of tactical components and guiding principles at its centre. Cape Town, for example, connected its digital strategy around data as an asset for decision-making with a series of concrete projects throughout the pandemic. This built up the basis and buy-in for more organization-wide data governance development. Montréal and Toronto have a digital charter or frameworks that stemmed from successful tactical work, and now serve as aligning platforms for deeper work around master data, data architecture, data flows, and other advanced data management projects.

These three aspects are all deeply embedded in Open North’s approach to data governance, and are the backbone of the tools and processes we use. From projects with large cities like Montréal to smaller towns from coast to coast to coast, this approach has served us and our clients well. Inspired by the ongoing conversation around the potential for synthetic data to be a privacy-enhancing technique, we are closing this blog off with a synthetic case study. It is a fictional amalgam of projects we’ve worked on that demonstrates the importance of the findings described above.

Synthetic case study: Harfield, ON

In the synthetic case study of Harfield, Ontario, Open North was approached by the town to help them move their data governance ambitions forward. In the wake of the pandemic, the Town of Harfield’s leadership recognized the need to increase their digital capacity so they could offer the kinds of digital services residents wanted.… But they weren’t sure where to start. The pandemic had made clear the importance of shifting into more online service delivery, but it had also highlighted the deeper and more complex technological, organizational, cultural, and processual changes necessary to support such a shift.

In response, they enlisted the help of Open North, who facilitated workshops with several of the champion business units. These workshops helped them to identify key challenges and opportunities. With Open North’s help, staff were able to clearly see the benefits of an organization-wide data governance strategy in supporting digital service delivery to residents. Through these workshops, town staff and Open North determined that the first step in developing the strategy was to conduct a data governance maturity and needs assessment across the town’s business units in order to identify key areas of concern and opportunity.

The central challenge identified through the assessment was a lack of clarity among staff around where data are stored, how they are stored, and how they may be accessed and used. To address this challenge, the strategy would involve a twinned process of data governance role and responsibility development in conjunction with internal capacity building on the value and function of data governance. Following this approach would ensure that organizational alignment and buy-in would be built up together with the necessary governance structures, thus not just providing the necessary support for the initial data governance project around data storage, but also laying solid foundations for future projects.

Having identified the central project of developing a clear data inventory and storage plan, Open North together with the initial team formed a data governance working group. This working group identified key data stewards in each business unit and began involving them in a series of workshops to build out knowledge and capacity around data inventories in particular, and their role within good data governance in general.

Over the following months, Open North continued working closely with the data governance working group to solve challenges as they arose, help make decisions about data set inclusion in the inventory, privacy, and sensitivity assessments of data sets, data architecture, metadata, and quality questions, and fine-tune roles and responsibility issues in the governance structure. By the end of the process with Open North, Harfield’s staff felt more empowered and motivated to tackle the broader data governance project and were already assessing next steps for a data warehouse project.