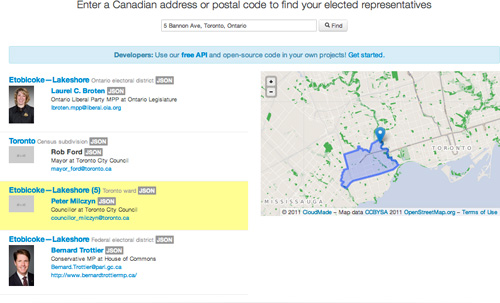

Earlier this year, we launched Represent, an open database of Canadian elected officials at the federal, provincial and municipal levels of government. Hundreds of citizens across the country use it to find their representatives’ contact information, and nearly a dozen nonprofits and civic innovators now depend on it to power their projects, campaigns and products. For example, the David Suzuki Foundation uses it in its online campaigns so that their supporters’ emails go to the correct Members of Parliament.

Represent has quickly become the largest database of its kind in Canada, with information on all provincial and federal representatives, and we already have municipal-level information for 40% of Canadians. In this post, we highlight some lessons we learned about getting data from municipalities, from our experience interacting with several dozen cities across Canada.

When things go right

In order to tell you what electoral districts you belong to, we need to know their boundaries. These boundaries are described in “geospatial” files. Sometimes, electoral offices and municipal governments publish these files on their websites. But most of the time, we have to email an authority to request the files. In the large majority of cases, we receive the electoral boundary data without question or comment, which leads to a first lesson:

If you don’t ask, you don’t get.

Too often, when government data isn’t readily available, citizens assume defeat. If you’re in this situation, give yourself a chance of receiving the data by sending a simple email request (and sometimes a short reminder a couple weeks later). If the information requested is non-sensitive, non-confidential and already exists, there’s a good chance you’ll get it within a few weeks time.

When things go wrong

Not all cities are familiar with the values of open data. Although in most cases we receive data without fuss, we must sometimes take extra steps like in the case of Vaughan, Hamilton and Whitby in Ontario.

Vaughan

Vaughan makes digital boundary data available only to organizations with whom the city has a contractual arrangement, like Microsoft or IBM. That policy didn’t make sense to us, so we completed the form to submit a formal request under Ontario’s Municipal Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (MFIPPA). Within a month, the files were sent to us on CD for a fee of $22.50 ($5 to submit the request, $10 for the CD and $7.50 for 15 minutes of labor). The city is now reviewing its policy relating to the digital spatial data in light of our request.

Hamilton

Hamilton charges $75 for their digital ward boundaries, subject to a license agreement that prohibits redistribution. We submitted a formal request as we did for Vaughan, to see if this license and fee structure would be upheld under MFIPPA. Our request was denied on the grounds that the information was already publicly available (section 15 of MFIPPA). The Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario (IPC) explained that a record is publicly available unless, according to the IPC, the cost is too high or the license agreement is too restrictive. We believe electoral boundaries should be freely available, because knowing who represents us is fundamental to our democracy. Thankfully, there’s hope that Hamilton’s data will be freely available, as the city council considers a new open data policy later this year.

Whitby

Whitby’s policy is to not release geospatial files at all. We submitted a formal request, which to our surprise was denied under section 15 of MFIPPA (like Hamilton), which means that the files are publicly available. However, in our correspondence with the city, staff clearly stated that these files were not publicly available. Furthermore, according to the IPC, Whitby must describe how to obtain files denied under section 15, which they did not. We’ve written to Whitby’s town clerk to clarify the situation. If we can’t resolve the issue, we may have to appeal their decision at a cost of $25. (Interestingly, no other access to information law in Canada charges a fee to submit an appeal.)

Conclusions

We should not interpret the above cases as rejections of open government or open data. Rather, the wide range of responses to our data requests suggest that governments’ attitudes towards open data are changing. These delays and misunderstandings can be seen as part of ongoing developments. Municipalities may be slow to add open data policies; however, these changes are happening.

At Open North we’ve learned that if you ask (and, in most cases, ask again) municipalities and other public bodies will be responsive and supportive. And if they’re not, we’ve learned that access to information laws are powerful tools, not only to release data, but also to change behaviour as in the case of Vaughan.

In the coming months, we will build new tools to make the Represent database more accessible to non-profits and advocacy groups. If you’re interested in using Represent in your organization, please contact us at info@opennorth.ca.