The case for structured data collection and management for more transparent public consultation

Whether it be for development of policy, approving a new capital investment, or debate of a civic issue, governments at all levels take actions to ensure that citizen’s voices and opinions are represented through processes generally referred to as public consultation.

Public consultation is in essence, a data collection exercise. Citizen and stakeholder input is channeled through a number of media, for instance by filling out surveys (online or in-person), attending town-hall meetings, or commenting on public documents online. These responses consist of information that must be managed, analyzed, and integrated into government decision-making. Observing public consultation through this lens highlights challenges for both citizens and governments to realize transparent yet meaningful public engagement.

Considerable attention to the front-end activities of the consultation (i.e. organizing meetings, creating surveys, inviting the public to participate) may be given by government. However, the treatment and documentation of feedback may leave some wondering: What happened to the information I volunteered?

Finding out how, or if, a citizen’s or stakeholder’s input was recorded and integrated into the decision-making process is not always clear. Clear and consistent data management practices are needed to ensure we always know the answer to this question.

What happens after a public consultation?

To illustrate, suppose you attend a public meeting where you have been asked by your provincial government to provide verbal comments on their proposed climate change strategy. You may ask yourself, what happens to transcripts from these meetings? How do they become tangible pieces of information which are then used to make policy decisions?

The Federal context

One of the ways one can find out what happened in a consultation is through official public consultation reports (sometimes called ‘What We Heard’ reports). These reports are created by governments departments to report back to the public on the outcome of a public consultation. These reports can come in the form of interactive websites, static websites with visual content, or static PDF documents. Some may even include analysis outsourced to a third-party. These reports face a challenge of balancing between simplicity and precision of a message; providing enough detail to encourage trust in the consultation process itself whilst fulfilling communications and public relations agendas.

In the Canadian context, a quick scan of some of these reports reveals an apparent focus on providing narrative summaries of conversations and the consultation process (which could be viewed as the data collection stage), at the neglect of any description of data collection, facilitation, and analytical methods. Examples can be found from the federal level down to cities and smaller municipalities. The reporting of ‘what we heard’ necessarily (or hopefully) involves analysis to identify major themes of conversation, with some choices on the most important themes to be represented in a final report. Because this process involves interpretation of data, clarity on the exact means of analysis is an important step to building trust in the consultation process itself.

Trust in the consultation process also requires an understanding of the follow-up; how government proceeds to make decisions based on consultation data. Documents containing decisions relating to a consultation can be scattered, which makes it difficult to figure out which recommendations from a consultation event were actually adopted. This issue has been raised at many levels of Canadian government. A recent report of the Office de Consultation Publique de Montréal which presents learnings from the organization’s 15 years of experience in public consultation, highlights the need for the municipal administration to improve their follow-up processes, given that there are no formal obligations for the city to follow-up with citizens post-consultation.

Challenges in collecting and managing with public consultation data

The foregoing underlines the need for government to better document and make known the analysis, methodology and decision-making that is used to transform public consultation data into actionable items. But even before this can happen, governments must collect and process data generated from public consultation. Diving deeper into some of these steps, reveals challenges that call for more consistent and replicable data management practices in government, while also improving data literacy for civil servants.

Sampling and data collection

Ideally, a public consultation is designed to solicit feedback from a wide range of citizens, representing the backgrounds and needs of the population as a whole. In practice, this is difficult because of sampling bias (see Rowe & Frewer, 2005). One reason for sampling bias is that citizens generally participate in public consultations on a voluntary basis. This makes it likely that those already with a vested interest in the consultation topic will be the most present and vocal, while others may simply opt out or be excluded. Indeed any democratic participation requires a certain level of effort – a common statistic to reference is voter turnout. Sometimes it is simply not worth the effort for a citizen to participate in a public consultation, resulting in people opting out of public debate. These factors may skew the representativeness of a public consultation (and thus its outcome).

The data collected during public consultation is an attempt to capture the needs and opinions of citizens and other stakeholders. Collecting, managing and analyzing this data can be difficult because oftentimes it is in the form of qualitative data such as text or audio. While this data is valuable to understanding people’s preferences, thoughts, or values, it is tricky to interpret. Dealing with qualitative data can become even more complex for in-person consultation events, where many participants may be talking at one time. Recording and structuring this data requires considerable time and expertise.

Processing and data analysis

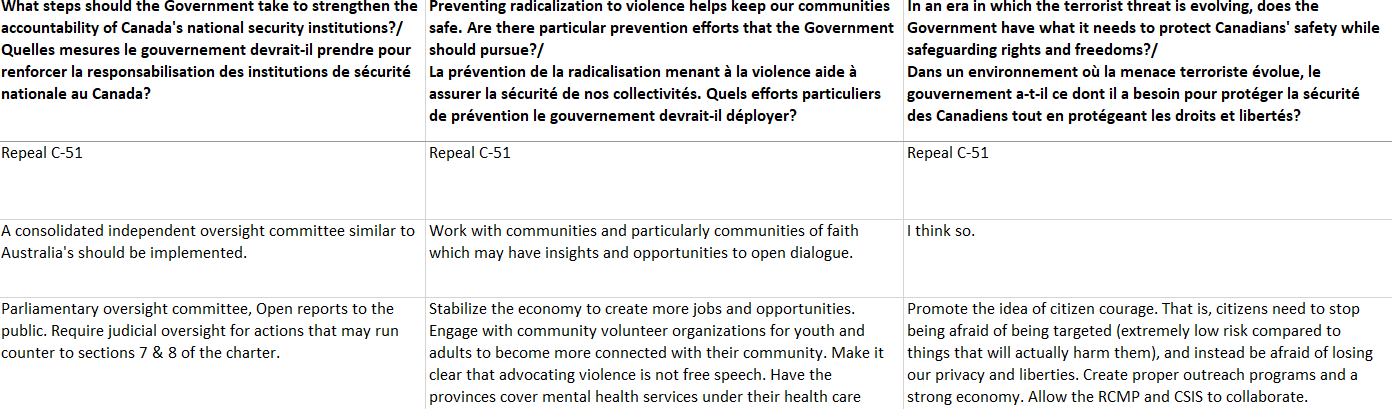

Now, after the data is captured and recorded, analysts need to clean up the “raw” dataset in order to remove errors, unnecessary information, or incomplete entries. To make things concrete, look at the datasets published for the Government of Canada Consultation on National Security Submissions. Exploring these datasets, one can find a number of repeated records. The data also contains responses to many questions, not all of which are relevant to the questions posed during the consultation.

Sometimes public consultation data can be difficult to interpret

Title of dataset: National Security Consultation: Responses Received via Email with links to attachments (05/11/2016 – 15/12/2016) Source: Government of Canada Consultation on National Security Submissions

Here, the analyst has some options in order to proceed. For instance, how will the analyst choose to identify the duplicate entries? How will he or she deal with the entries that do not contain answers to the relevant consultation question? Will those also be removed? Do they need to be weighted?

Even at the initial stages of analysis, the approaches to treating this data can vary, thus impacting how what was actually stated, spoken, or contributed to a public consultation is actually represented. Additionally, without proper documentation of the steps taken in analysis, the analyst risks reducing transparency around the decision-making process for both internal and public audiences. This risk applies to any treatment of consultation data, whether it be at a small municipality, a province, or Federal institution.

The need for consistent and replicable data management practices

Managing public consultation data throughout all the stages of consultation is complex. It can require collecting large volumes of messy or unstructured information, from a variety of channels, while processing qualitative data and at the same time, identifying and treating sampling issues. Governments do all of this on top of the presumed responsibility of serving and engaging the public, managing competing interests and political agendas, and upholding a level of fairness and transparency in their decision-making processes.

These challenges raise the need for government to work on developing and implementing clear, consistent and replicable data collection and management methods for public consultation. It also requires that civil servants are equipped with the skills, capacity and knowledge to manage not only the initial activities of the consultation, but also effectively manage the data generated, throughout the lifecycle of the consultation.

OpenNorth’s recent experiences

OpenNorth’s experience in public consultation comes through a number of projects in Canada and internationally, to support governments in operationalizing transparency and accountability through consultation processes. At the Applied Research Lab, we have worked with the Privy Council Office (PCO) of the Government of Canada to develop a workflow for processing and analysing qualitative consultation data (text). This involved the use of free, open source libraries to perform content analysis and the processing of tabular data. These activities brought up new issues, namely the need for standardisation of data in qualitative consultation data, where we addressed these issues through a proposed data model. Building on this success, OpenNorth is working with the PCO to create digital learning tools to help civil servants improve their data literacy skills, specifically for public consultation data.

We are also working to support the development of public consultation capacity in Ukraine with the National Democratic Institute, by providing assistance on planning, facilitation, data, and analysis of consultations. OpenNorth is working to build capacity by providing tools and frameworks for implementing public consultation pilot programs. Through these projects, and building on our past work in participatory budgeting, we hope to continue supporting governments in ensuring their public engagement activities are transparent and result in a meaningful use of the data collected.

Work cited:

Rowe, G., & Frewer, L. J. (2005). A typology of public engagement mechanisms. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 30(2), 251-290