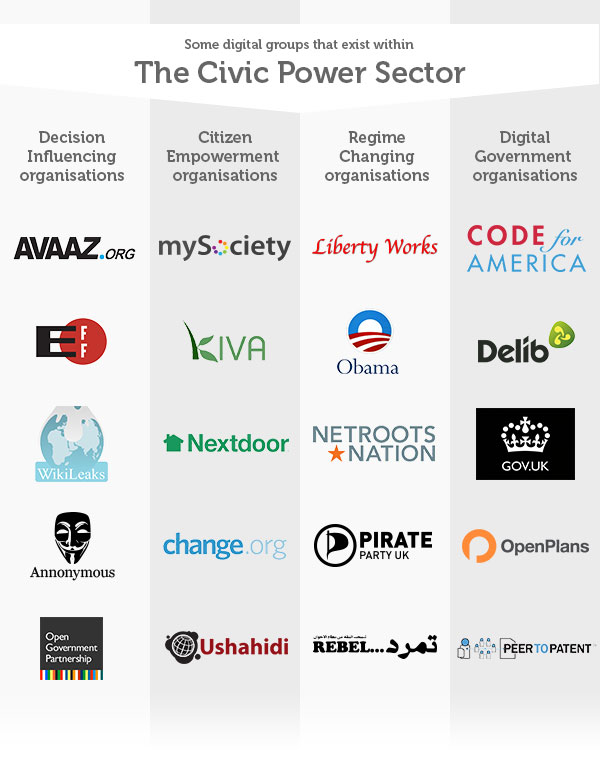

In a recent blog post, Tom Steinberg of mySociety describes the “civic power” sector as the sector that serves “people’s need to obtain and deploy power.” He segments it into four parts:

- Decision influencing organizations try to directly shape or change particular decisions made by powerful individuals or organisations.

- Regime changing organizations try to replace decision makers, not persuade them.

- Citizen empowering organizations try to give people the resources and the confidence required to exert power for whatever purpose those people see fit.

- Digital government organizations try to improve the ways in which governments acquire and use computers and networks.

Steinberg offers a few example organizations to help clarify the segments:

What kind of civic power and over whom?

According to the brief definition of “serving people’s need to obtain and deploy power,” nearly every online retailer makes the cut. Amazon allows customers to rate and review products, giving them the power to influence the producers and reduce the information asymmetry between consumers and producers. I don’t think it’s controversial to state that Amazon and WikiLeaks belong to different sectors.

The problem with the definition is that it makes no attempt to scope the term “power.” At the risk of making controversial statements, the sector is about:

- upward power (citizens exerting power over governments) not downward power (governments exerting power over citizens)

- exerting power over institutions (like a rights watchdog does), not over individuals (like an influential does)

Although these additional constraints clarify the definition of the sector, they still don’t exclude Amazon. For now, we can say that Amazon primarily serves people’s need to acquire things, and only secondary serves the need to exert power over producers. However, I am curious to see how else we can scope “civic power” to more precisely bound the sector.

Shortcomings in categorization of the civil power sector

Classifying Anonymous under “decision influencing” seems very tongue-in-cheek to me, because its most visible activities – hacking or attacking the websites of the organizations it wants to change – is a much more extreme form of influence, closer to coercion.

Putting Avaaz and the Open Government Partnership in the same basket is another surprise. Avaaz mobilizes millions of people to sign petitions and donate funds to specific campaigns. The OGP, on the other hand, accomplishes its mission by facilitating its participating governments and civil society organizations. One approach is confrontational; the other is cooperative.

As noted in the original blog post, the “digital government” category may be a subcategory of “decision influencing,” which becomes very crowded and diverse in this framework.

Another way to split the civic power sector

I’d like to propose a different segmentation that brings out some important differences while retaining some of the previous distinctions. As an individual, you can change the behavior of a decision-maker or an organization, like a legislature or government, in many ways, including:

- become a decision-maker (get elected, for example)

- cooperate with a decision-maker (educate, partner)

- confront a decision-maker (petition, whistleblow)

- coerce a decision-maker (attack, blackmail)

- withdraw from any relationship with the organization (boycott, exit)

1. Become a decision-maker

The so-called “civic power” sector is concerned with helping others do the same. Under this new segmentation, the example organizations now break down as follows. All organizations within Steinberg’s ”citizen empowering” category are reassigned, which is not surprising, given that ”citizen empowering” was synonymous with the “civic power” sector as a whole.

It may come as a surprise to see Kiva alongside political parties and election campaigns, which are clearly about helping people become decision-makers. But Kiva does help people become decision-makers; anyone with $25 can become a lender on Kiva and decide who to loan money to – a role usually fulfilled by banks, governments and other large institutions.

2. Cooperate with a decision-maker

There are many forms of cooperation, including:

- offering products and services to institutions (Delib)

- collaborating with institutions to address problems (OpenPlans)

- convening institutions (Open Government Partnership)

Code for America, for example, pursues multiple strategies to change government culture:

- Installing fellows within government to spread culture, understand problems, design solutions

- Encouraging residents to work with local government to improve services with technology

- Preparing companies to partner with and sell to government

- Facilitating a peer network of innovators inside government

3. Confront a Decision-Maker

In this new categorization, Change.org, an online petition platform, joins the other organizations that change institutions via confrontational means. In this framing, more kinds of organizations, like class action law firms, find a place within the civic power sector.

4. Coerce a decision-maker and 5. Withdraw from any relationship with the organization

We can find additional examples for the last two categories: coercion and exit. For example, any organization that reduces a person’s dependency on, or interaction with, an institution fits the “exit” category; I slot Nextdoor here as it helps make neighbors less dependent on government and the private sector and more dependent on each other.

As with any categorization system, some organizations fit better than others. For example, the use of Ushahidi’s technology may support one kind of interaction or another: CrowdMap can be used to crowdsource violations committed by a ruling party during an election (confrontational) but also to report missing people in crisis response (cooperative).

An organization may also deliberately pursue multiple strategies. mySociety (UK Citizens Online Democracy) helps people demand better from institutions, while its subsidiary (mySociety Ltd) helps institutions better serve the public. Open North also bridges these two.

How would you segment the sector?

The categorization I propose focuses on the strategies for changing institutions, but that is not the only way to segment the sector. We might think about where an organization’s power comes from: for example, does the organization have worker power, like a labor union, or purchasing power, like a private foundation? Or we might take an activity-based approach, which may include tool building, policy research, market development, mobilization and reporting.

Thinking of new ways to segment the sector will offer a more complete picture of this diverse sector. Indeed, foundations are conspicuously absent from the discussion thus far – which includes blog posts by Global Integrity’s Nathaniel Heller and the World Bank’s Tiago Peixoto – despite foundations funding much of the sector’s work.

Contact Open North today to learn more about our Civic Engagement expertise.