In August, we shared our experiences requesting digital electoral boundary files from municipal governments for Represent, our open database of Canadian elected officials. Represent uses this data to tell you what electoral districts you belong to.

Nonprofits, civic innovators, and citizens often want access to this raw data, so we go one step further to make it available: once we receive data, we ask governments for permission to share these files with the public through a public server.

In the previous post of this series, we learned that “if you don’t ask, you don’t get.” But once you have the data, what can you legally do with it? In this post, we highlight some bumps in the road to open data licensing across Canada as well as a few important advancements.

Why license agreements?

In Canada, government information is automatically protected by copyright. This differs from the United States where works of the federal government and of some state governments are automatically within the public domain. Canadian governments can, however, relax the constraints of copyright through license agreements.

At a minimum, a license agreement allows you to make private use of the data. An open data license, on the other hand, typically grants permission to use, modify and distribute the data or your modifications. We don’t have the space to get into fair dealing here, but suffice it to say: if you have government data without a license, you may not have permission to use it! That’s why we ask governments for explicit permission to redistribute the data they send us, or ask for an exemption to a standard license that otherwise forbids distribution.

Humble beginnings: Nanaimo’s open data portal

Nanaimo was the first city in Canada to launch an open data portal in 2009, with Vancouver following a short three months later. It was Vancouver’s data license, however, that was adopted by most cities to follow – nearly a dozen, including Edmonton and Ottawa.

The Good

Having this sort of de facto standard license is good for licensees, because they can spend less time reading licenses and more time using data. It’s also good for new cities adopting open data policies, as they can spend more time preparing data and improving their open data strategy. That’s the good.

The Bad

Unfortunately, the Vancouver open data license (and its copies) has some oddities within it. David Fewer and Kent Mewhort of CIPPIC (former Open North board member) detail some of them in a 2010 recommendation to the City of Ottawa. For example, Ottawa’s Open Data Terms of Use stipulates that, “If you distribute or provide access to these datasets to any other person, you agree to ensure they agree to and are bound by these Terms of Use.” This clause is not only onerous; as Kent Mewhort describes elsewhere, “it may even be infeasible for you to comply with it, as minors without the capacity to agree will never be bound by the agreement.”

That same clause applies to the “original or modified form” of the dataset, thereby imposing a “share-alike” obligation. This means that if you add value to a dataset from the city, you can only share your new dataset under an open data license consistent with the city’s. This is bad for business: it’s hard to start a company that builds on open data if you need to share your value-added data with your competitors. As CIPPIC explains in another document, this clause likely arose out of misconceptions about share-alike.

We believe these and other issues are oversights, that merely speak to how nascent open data licensing is. (We don’t believe Vancouver and others were making a conscious effort to exclude minors.)

The changing landscape of open data licensing

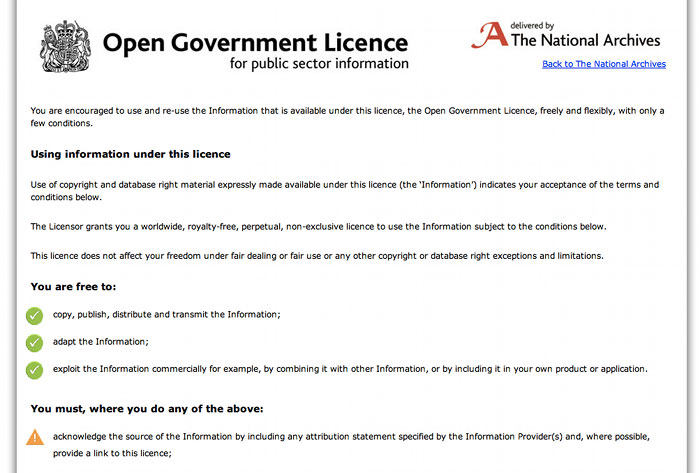

Data licenses have had time to mature since 2009. In the past year, more and more Canadian governments have adopted licenses based on the UK’s Open Government License for Public Sector information, which clearly outlines rights, obligations and exemptions. This easy-to-read license is now in use by British Columbia, Toronto, Region of Waterloo, Region of Peel and Grande Prairie No. 1. In our correspondence with municipal officials in the process of drafting new open data licenses, it’s the license we suggest most often.

The Township of Langley and City of Surrey instead adopt the Open Data Commons Public Domain Dedication and License (PDDL), another standard license which CIPPIC reviews favorably in this draft document.

Moving forward

We must remember that municipalities build their datasets with taxpayer funds. As a public good, access to non-personal, non-confidential data should not be limited to those with the necessary time, knowledge and financial resources. Represent is an example of a useful tool that can be built when Canadian cities open up their data. As more cities adopt open data, organizations like Open North can spend less time writing emails and access to information requests, and more time helping others make full use of the data in their own projects.

The Sunlight Foundation has compiled Guidelines for Open Data Policies which serves as an excellent starting point for governments or anyone interested in these issues. One of the guidelines is that “information released by the government should be sticky: once released, it must remain ‘findable’ at a stable location or through archives in perpetuity.” Open North strives to respect this principle in its own projects, by making the data they use available via APIs like Represent’s and via direct download. These are our ways of ensuring that the public will have access to government information over the long-term.

Want to learn more about our work? Browse our publications to learn more.